Considering CO2 as an industrial waste: a radical approach to zero emission

Carbon dioxyde (CO2) is a colorless and odourless gas. Nowadays, it is mainly appears as a byproduct of combustion. The energy produced by this combustion allows humans to do all sorts of things: run turbines, cause chemical reactions, activate a piston and make a car move, heat a house...

The problem is that CO2 absorbs some of the infrared radiation emitted by the Earth, which previously went back into space. So, Earth is warming up, and that's a problem for humans.

Raw materials, energy and pollution

This section is only a very partial summary of a class given by Jean-Marc Jancovici, you can find the full version of his excellent course at Mines ParisTech here (in French).

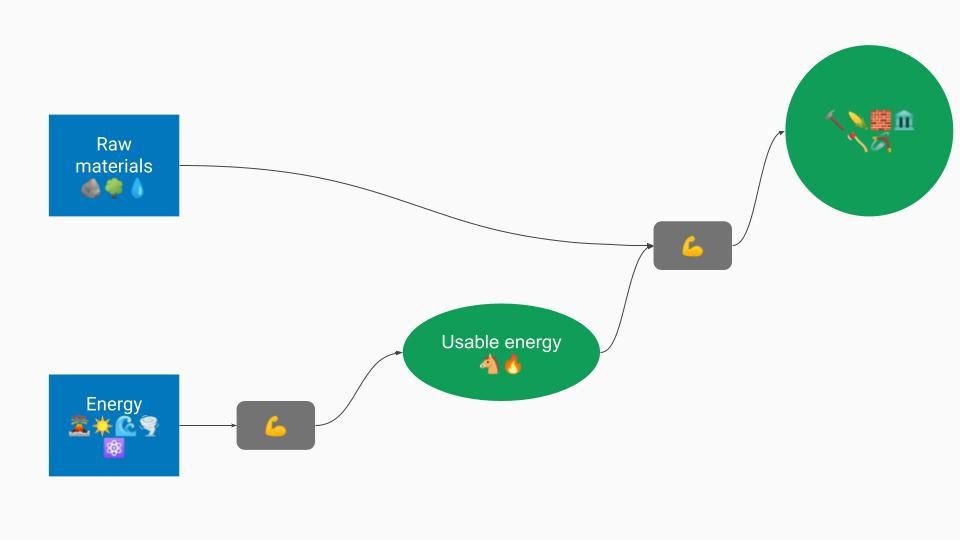

Our civilization is physically based on raw materials, which we extract from our environment and transform with energy, to make final products that are useful to us.

Some of the final products are used to increase future production, increasing our ability to extract raw material, or the amount of energy available.

In -500 000, hunter-gatherers used their physical energy to gather flint (raw material extraction), collect wood which they burn (transformation of natural energy into usable energy), to then make tools, heat themselves, or cook their food (final products).

This system works particularly well, and as time went on we had more and more energy at our disposal, so we produced machines that we could redirect to production, in order to increase the amount of energy and raw materials available.

Today we use energy and terrestrial raw materials to produce absolutely everything around us: our food, our water, but also our cars, our roads, our drugs, our smartphones, our buildings, our clothes etc...

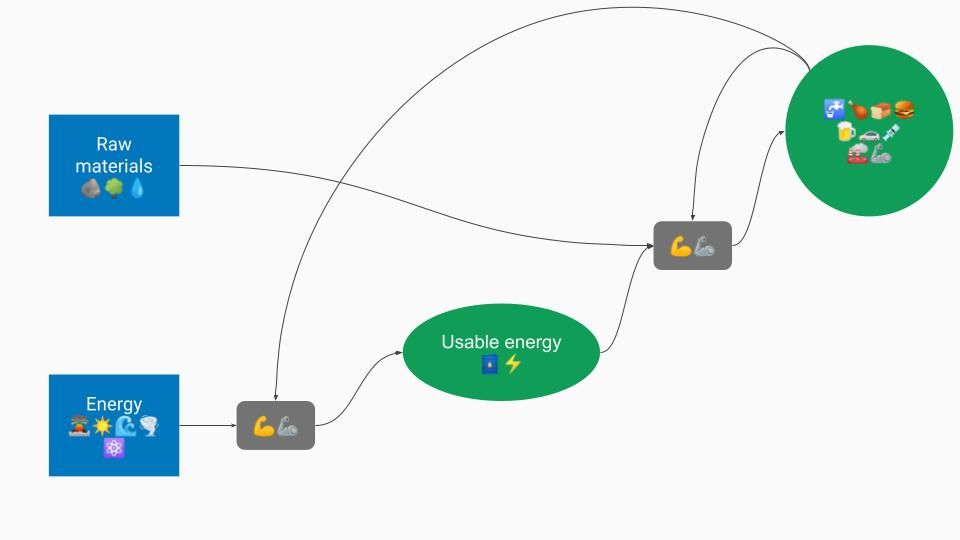

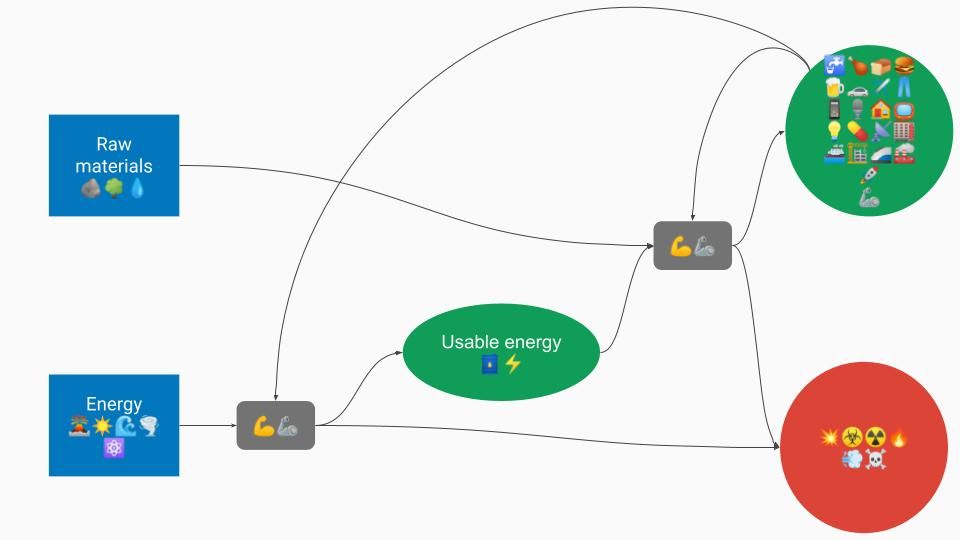

This process is obviously incomplete, because in addition to the desired products, we also get undesirable products.

We set up systems to transform energy and make it usable, and these systems produce negative effects when used on a large scale:

- Coal: by burning it, we can produce heat (energy, which we want), CO2 (which we don't want), and a lot of particles that are more or less harmful.

- Oil: we can extract gasoline from it, which we burn in our engines to make our cars move. In the process it produces CO2, NO2, and other undesirable particles.

- In nuclear reactors, a neutron collides with a uranium nucleus, which splits: we get energy which we use to heat water (what we want) and other atomic nuclei (more or less dangerous).

Raw materials extraction of raw materials also produces a number of undesirable products, such as soil or groundwater pollution, deforestation, air pollution etc.

Undesirable products are harmful to humans and the environment, and they have the opposite effect of tools used for production: they decrease the stock of available raw materials and impact our ability to transform energy or use it to build valuable final products. They therefore endanger the future, in addition to being immediately problematic.

Desirable products, undesirable products

We can see a dilemma appear: we want to produce more and more desirable final products, have more and more energy for our daily needs, without increasing undesirable products, or at least while limiting their increase.

Strongly and weakly undesirable

Not all products are undesirable in the same way: some are strongly and immediately undesirable, like industrial pollutants or nuclear waste.

For these products, even if their volume is minuscule, their danger is obvious: the lethal dose of plutonium is a few micrograms. We therefore invest a lot in their treatment, and we don't let even the slightest fraction escape into the environment.

Industrial pollutants are another example: everyone immediately sees the problem with releasing pollutants like ammonium nitrate (the substance that caused a factory in Toulouse to explode in 2001) into nature. We therefore put in place very strict regulations to oversee the treatment of these undesirable products, and it is illegal to discharge them into nature.

Some undesirable products are less visible, and only become problematic when present in large volume. This is the case of greenhouse gases, which only have an impact when they are emitted in billions of tonnes. This is also the case of plastic waste for example.

For these weakly undesirable products, it is much more difficult to see the point in regulating them, and their treatment appears at first to be an unnecessary cost. It is easier not to take them into account, and once their volume becomes significant it is difficult to change habits.

Well-managed strongly undesirable products, and ignored weakly undesirable products

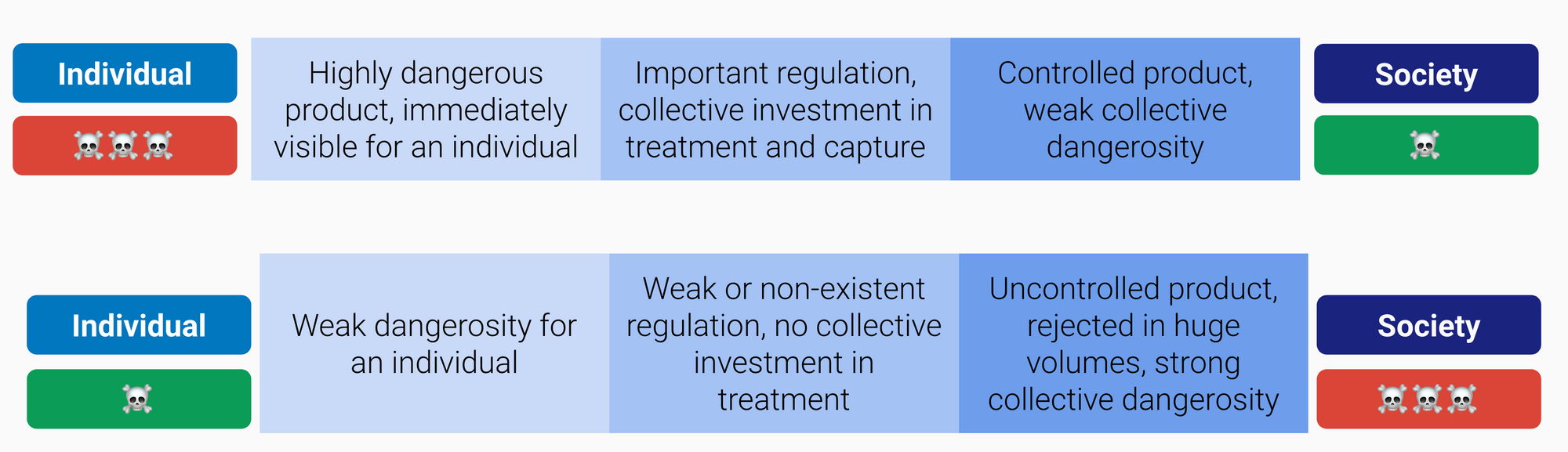

We first put in place regulations for strongly undesirable products, for which the danger is obvious. These policies having been put in place a long time ago, the real "dangerousness" of a product expressed in terms of lethality, or number of deaths per year, has little to do with its initial danger, or perceived danger.

We start with the real, individual danger posed by a product, and we extend this perception to the community. A product that is very dangerous for the individual is well taken into account collectively, it becomes illegal to discharge it into the environment, and we collectively invest in its treatment. Through collective actions, we reduce the danger posed by a product, which is handled under very strict conditions by professionals, and with which the citizen is never in contact again.

Conversely, a product that is weakly undesirable, or poses a limited danger individually is poorly taken into account collectively, even in large volumes. We invest little in its treatment, even if the collective danger, given the copious amount of product, becomes almost existential.

In the public debate, strongly undesirable products often elicit reactions that have no connection to their actual level of danger, while weakly undesirable products elicit apathetic reactions at best, or indifference.

A classic example in the energy sector is nuclear power, and particularly nuclear waste: extremely dangerous products that are present in very small quantities, with an extremely well developed waste treatment industry, in which we have collectively invested billions. Result: 0 deaths per year.

Coal, on the other hand, whose extraction and combustion produce particles that cause about 23,000 deaths per year in Europe alone (report available here), is not perceived as dangerous.

Perceived danger is therefore strongly linked to the individual danger of the product, there is a form of rationality. But it is not at all linked to the real, collective danger, which is influenced by regulation policies and waste-treatment rules.

We have collectively prioritized what appeared to be the most immediate risk from an individual point of view, and thus contained lethal industrial waste before addressing the problem of an odourless and harmless gas.

Moving from a small amount of a strongly undesirable product to a large amount of a weakly undesirable product is often advantageous

Despite physical reality, there are two types of benefits to moving from a strongly undesirable product present in very small quantities to a weakly undesirable product present in very large quantities.

First, an economic benefit: in general, a strongly undesirable product will be heavily regulated, the producer will be responsible for its treatment, which will probably cost a lot, and if it is released into the environment, the producer will risk criminal prosecution.

A weakly undesirable product, on the other hand, is likely to be weakly regulated, and its release into the environment will cost the producer nothing.

The cost then shifts from the producer to society as a whole, a classic example of a negative externality.

There is also a political benefit: the perception of danger being biased by the individual danger of the product, you can appear as a benefactor by getting rid of a highly toxic product, even though you are introducing a slower and more diffuse catastrophe.

Industrial waste | CO2 | |

Undesirable volume | 1 gram | 1 ton |

Perceived dangerosity | Very strong | Weak |

Real dangerosity | Very weak (nuclear : 0 death in 2020) | Strong (global warming) |

Handling, treatment | Completely contained | Uncontrolled, rejected in the environment |

Regulation | Extrêmement forte | Weak or non-existent |

Waste disposal cost | Very high | Low |

Who pays? | The producer | Society |

You no longer bear the cost, which falls on society, and the perceived danger of your solution decreases, so you can be re-elected. So everything is better, except that you have potentially increased the real danger.

CO2 : a major pollutant, but weakly undesirable

In summary, we have raw materials and energy that we extract and transform to obtain desirable products for humanity. In doing so, we generate undesirable products that we want to limit. These products being more or less undesirable, we prioritize and first handle strongly undesirable products.

Today, we are at a scale where weakly undesirable products are present in such quantities that they become a major issue for our future. We have collectively built regulations and institutions focusing on strongly toxic products, and in doing so have overlooked weakly undesirable products, of which no one feels responsible for.

We manage strongly undesirable products fairly well (again, 0 deaths from nuclear power for decades), but we are terrible at managing weakly undesirable products.

CO2 is the perfect example of a weakly undesirable product: completely invisible, completely harmless in small doses, it can be released into the environment without any consequences. It takes a gigantic amount (billions of tons) to see its impact.

The reality is here : CO2 is THE undesirable product of the 21st century, the number one pollutant, the one that is most urgent to get rid of.

A weakly undesirable product, weakly desirable regulations

Switching from a strongly undesirable product in small volume to massive amounts of CO2

As CO2 is weakly undesirable, public reactions to more CO2 in the atmosphere are generally indifferent.

The perceived danger of a product, and its disconnection with the real collective danger, makes it quite simple to exchange a strongly undesirable product, such as nuclear waste, for CO2 emissions. This model is simplistic, but explains well some recent choices, particularly in energy.

This is exactly what happened with the closure of the Fessenheim nuclear power plant. It was decided to close a nuclear power plant in perfect working order, for an electoral agreement and to gain a communication benefit, counting on the fact that the public would appreciate the disappearance of a strongly undesirable product. To compensate for this closure, coal-fired power plants had to be reopened, which emit large amount CO2 and other harmful particles, weakly undesirable products.

This is also what is happening with the notorious Energiewende in Germany. In 2010, the German government produced a document describing Germany's strategy to achieve carbon neutrality in energy production. Initially, nuclear power was included in this strategy and used for the transition.

After the Fukushima accident in 2011, nuclear power was removed from the strategy, and the focus was placed on renewable energy sources. In order to reach the same energy production and make up for the intermittency of solar and wind power, the use of fossil fuels, and therefore CO2 emissions, had to increase.

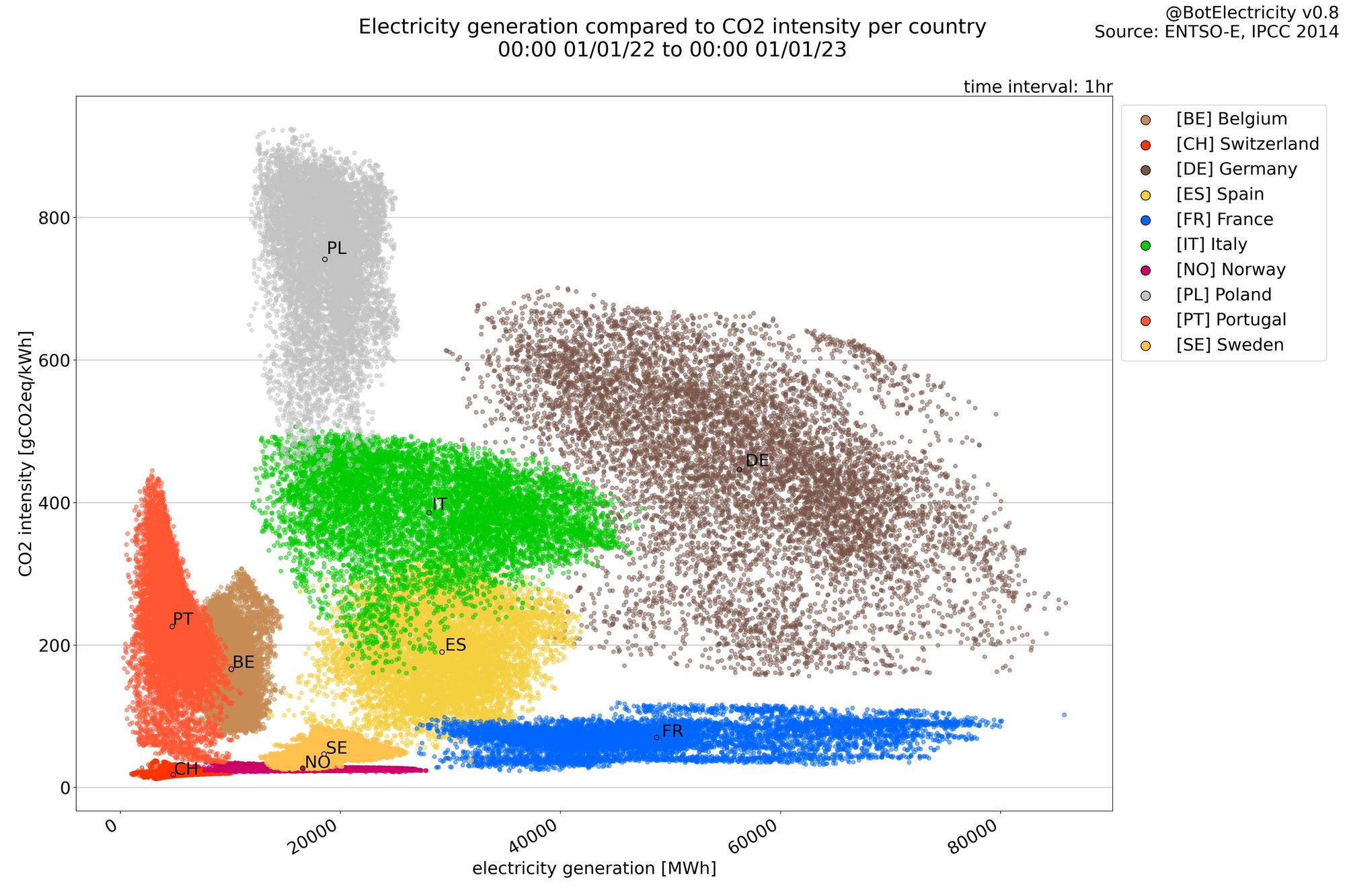

Now, Germans use coal and "transition" gas, and their electricity is on average 10 times more carbon-intensive than that produced in France.

They have therefore traded a highly undesirable but completely controlled product with weakly undesirable but massively emitted CO2, with a major collective impact.

The multiplication of criteria makes the decision impossible

We see that regulation plays a major role, as it illustrates what is collectively considered toxic. It allows for arbitration between different alternatives and counteracts human biases exploited by communication.

We have sometimes put in place counterproductive regulations that put products of different hazardness on the same level, and that do not allow for prioritizing CO2 reduction.

A commendable initiative of the French State and local authorities is the establishment of "green budgets". These budgets are supposed to guide public action in the ecological transition, by assigning to each expenditure an impact (positive / negative) according to six major environmental objectives: fighting against climate change; adaptation to climate change and prevention of natural risks; water resource management; circular economy, waste and prevention of technological risks; fighting against pollution; biodiversity and protection of natural, agricultural and forest spaces.

The multiplication of criteria and the idea of putting all "waste" on the same level, without taking into account the danger they represent makes this tool difficult to use concretely, and does not allow it to give its full measure in terms of fighting against climate change. It would be necessary to quantify the carbon content of each expenditure, and potentially compare it with the hazard of the alternative.

Regulations that get the wrong criteria: prioritize CO2

This summer, we saw the problem of discharging nuclear power plant water into French rivers.

This is not a problem of nuclear safety, nor fundamentally a problem of water temperature: we have built nuclear power plants in much hotter places than the Gironde (like Saudi Arabia), and the water comes out at a much higher temperature, simply because the ambient air is at 40 degrees.

No, it's a biodiversity problem: the fact of discharging slightly warmer water makes the fish downstream unable to reproduce and puts them at risk.

This illustrates a major problem of prioritization. We have a carbon-free energy source (nuclear, but also wind or hydro) that is forced to reduce its production to protect fish, birds or other animals. To ensure energy supply for humans, we instead restart a gas or even coal-fired power plant.

We have replaced a strongly undesirable product (warm water and dead fish) with a weakly undesirable product (CO2 and fine particles). Dead fish are immediately visible, CO2 is not, so politically this works out well. Physically and in the long term, it is more debatable.

Have we replaced a strongly undesirable, but well-managed product with a weakly undesirable, but uncontrolled product?

Another example is the energy regulation of buildings: in France, the "energy diagnosis" of a house is based on its energy consumption per square meter and per year. The rating influences the value of the house, the possibility of renting it, and the eligibility for certain aids.

Except that the criterion is counter-productive: it takes into account the amount of energy, but does not take into account its type, and therefore the carbon content of energy. It is possible to have a concrete house heated with wood or coal that obtains a better rating than a wooden house heated with carbon-free electricity.

The regulation is using the wrong criterion and pushes us towards a false solution.

CO2 should be treated as industrial waste

So what can be done? We must consider CO2 and other greenhouse gases as what they are: undesirable products that put our collective existence at risk, that we must get rid of them.

We should imitate what we have done for other pollutants linked to the industrial era, and consider CO2 as an industrial pollutant, just like asbestos, ammonium nitrate or chlorofluorocarbons, these gases that are destructive to the ozone layer, which we were able to get rid of successfully.

Treating CO2 as an industrial waste forces the producer of the gas to face their responsibilities, forces us to invest collectively in the treatment and capture of CO2 that we are bound to emit, and will ultimately allow a zero-emission trajectory.

Obviously, we cannot create and enforce such a regulation overnight, but a very good first step would be to quantify the carbon content of the products we consume. That would materialize the fact that our choices have an influence, allow us to compare alternatives objectively, and to break the distance that can exist between the public and CO2 emissions. This carbon labeling would be similar to what is done for food products.

This would also avoid manoeuvres where we switch from an energy source seen as "dangerous" to an energy source more acceptable by the public but highly carbonated.

By relying on this labeling and precise measurement of the carbon content of products, the European carbon market coupled with a carbon compensation mechanism at the EU's borders would force industrialists to align with rigorous standards and, once again, enable a transition to less carbon-intensive products.

At the moment, this compensation mechanism established by the EU is limited to certain products, but it must be quickly extended to all manufactured products.

The carbon market is only a first step: nobody would accept that companies have a "right to emit mustard gas into the environment," which would be bought and sold on a stock exchange. It is prohibited, period, and it is up to industrialists to make arrangements to treat their toxic products, before any potential releases into the environment.

This is where the paradigm shift takes on its full significance: if CO2 is an industrial pollutant, we must create regulations that force industries to invest in their emissions' treatment and impose heavy fines on those who do not comply with the law. It will inevitably be costly, but it is simply a rebalancing: costs, instead of being supported by society, will be supported by the CO2 producer, who may potentially pass them on to their customers. Highly carbonated products will not only be more expensive but also less attractive to consumers due to carbon labeling.

CO2 capture technologies exist but are still a at very early stage, and must be scaled. The cost of CO2 on the carbon market must gradually increase, with an overall compensation mechanism at the EU's borders extended to all manufactured products.

Carbon labeling of products must be standardized and made mandatory, in order to allow consumers to make informed choices, which will further push towards decarbonization.

Finally, zero-emission goals must be accompanied by a commitment to consider CO2 as an industrial pollutant and a willingness to include it in the law.

By considering CO2 as an industrial waste, we turn this colorless and odorless gas into a bright issue, and the major risk it poses to our societies becomes visible. This paradigm shift is essential in implementing the strong measures necessary to limit this risk.